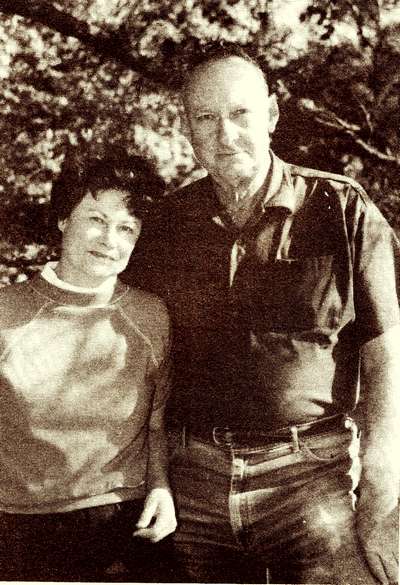

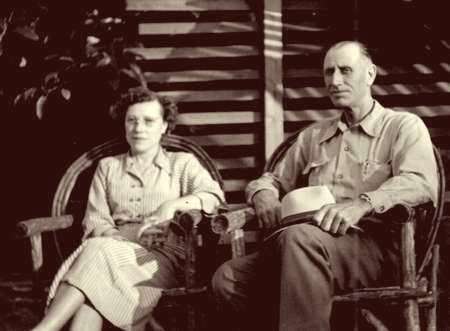

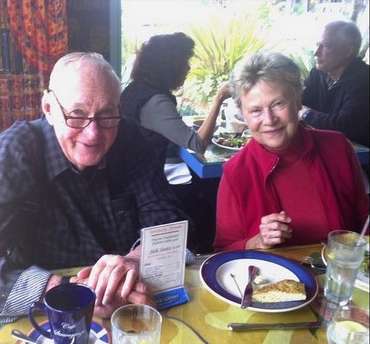

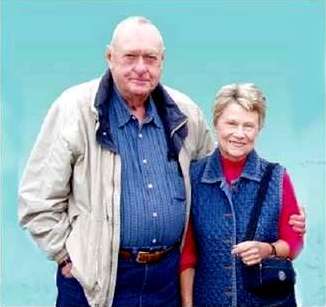

Shirley Murphy and her husband Patrick Murphy, 1992

Shirley Murphy and her husband Patrick Murphy, 1992

Autobiography: Shirley Rousseau Murphy

This appeared, with some of the pictures, in Contemporary Authors, Vol. 411, Gale, 2018. The part of it prior to the Update section was originally published in Something About the Author Autobiography Series, Vol. 18, Gale, 1994.

*

The sounds from my childhood are the hush of a horse's hooves over new green grass and the thud of hooves on a narrow dirt trail, and always the crashing of the sea like a huge and hollow heartbeat. When I was very little, the sea, six blocks away, lulled me to sleep at night. I was an only child, no brothers or sisters, and did not always feel at ease with other children. The first home I remember, in Long Beach, California, was a small apartment in a row of one-story boxes. They were plain and ugly, and they marched around a central lawn like an old-fashioned motel. I slept in the living room, first in a crib and later on a bed that folded down out of the wall and folded up again in the morning behind closet doors.

My mother was an artist, and as a baby I played beside her easel while she painted. She was just out of art school then, and only beginning her painting career.

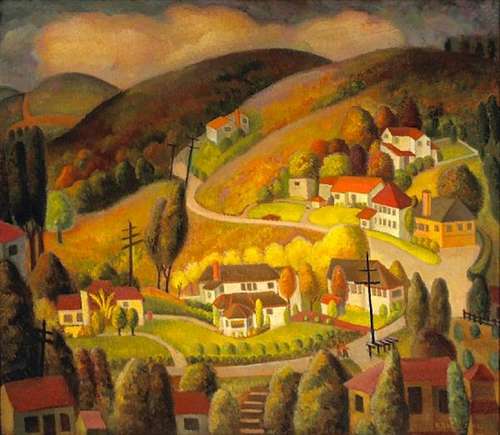

In all the places we lived when I was a child, our walls were filled with her portraits and later with her bright impressions of California's green hills, red rooftops, boat harbors, and little farms. These paintings were, for me, like windows into the world, vivid snatches of color and beauty from beyond our walls. My mother was Helen Rousseau, and until the mid-1970s she exhibited oils and watercolors up and down the West Coast. Her work is still represented by her agent in Carmel; and I have many of her paintings, so those early years are always fresh for me.

Next door to our little apartment was my grandparents' house. It was another plain box, but three stories tall and covered with green vines so thick that no brick showed through. Vines would have covered the windows, too, if my grandfather hadn't kept them cut away. He would go into each room, opening one window after another, and with a big pair of shears he would clip off the creeping green tendrils. My mother's father was a small, round, gruff man who always wore a three-piece suit and white shirt and tie even when he was working in his garden. He was a man of plain tastes, he didn't like social events, and if he'd had his way he would have lived in one room with only a cot and table. He had built the tall house not for himself, but for my grandmother, and to have room for their grown-up children when they came to visit.

Shirley with her mother, Helen Rousseau, Long Beach, California, 1928

Shirley with her mother, Helen Rousseau, Long Beach, California, 1928

My grandmother made delicious chowder; she cooked everything to perfection. She was a Virginia girl who liked to have company and to visit. She took me to children's plays and she read to me, she sewed for me, and I played in her kitchen while she baked pies and rolled out homemade noodles on the big table and cut them into long strips. I could hardly wait for the stewed chicken and noodles to reach the table.

But all the pleasures in that house did not come from culinary joys. It was filled with other wonders, too, with visual riches to set a child dreaming.

My grandmother had gone to Europe years before I was born. She brought back Chinese rugs patterned with dragons and flowers, and dark Chinese chairs and tables with dragons carved round the legs. In my solitary games I rode winged dragons and I talked with dragons. I had no notion that one day, years later, I would write books about dragons and invent a world for them.

In that house was a windup Victrola and a mahjong game made of painted and carved ivory pieces. There were tiny miniature books all bound in soft leather. There was also a carved wooden monkey on the wall by the front door that played music when you hung a hat on his feet, and an iron tiger as big as a house cat. If I stayed with my grandparents overnight, part of my going-to-bed ritual was to put food in the tiger's mouth. I always saved part of my dinner for him. The next morning my offering would be gone; the tiger had eaten his supper. I never did catch the smile on my grandfather's face.

In the attic of that house I played among the old trunks trying on my mother's gold-sequined flapper dress from her college days, or draping myself in the soft, brown deer hides from my grandfather's hunting. I didn't guess that attic would one day be a part of my children's stories.

When we went to see my father's parents on their farm south of Long Beach, I played with my two boy cousins in the orchard, running down long, shadowed tunnels beneath the walnut trees. My father's mother had been a pioneer child. She had traveled from the East Coast to Montana in a covered wagon and had fought off robbers with her rifle. It was on their farm that my dog Sport was born. He was my birthday present when I was four. He was part springer spaniel and part Pekinese, an amusing combination, but he grew up to be as big as a springer. He was my constant companion for many years, at home and then at the stables when, shortly after my fourth birthday, I began to learn to ride.

With father, Otto Rousseau, and grandmother, Helen Hoffman, Long Beach, California, 1931

With father, Otto Rousseau, and grandmother, Helen Hoffman, Long Beach, California, 1931

My father taught me how to saddle and mount a horse, how to hold the reins, and how to give my horse signals. But my most diligent teacher was a little white mare named Patsy. She was what we called a school horse. She was patient with small children and she knew how to teach a child. If I pulled her mouth too hard, she would stop still and jerk the reins until I eased my hold on her. If I started to fall, she would stop and wait for me to get settled. She took care of me and did not allow me to develop bad habits. My father had borrowed her just to teach me. In her lifetime, Patsy taught many children to ride. We had her for nearly a year before she went home again.

*

So from age four on, I was a dirty-faced stable child. I went to the stables with my father every morning. I would be out of bed and dressed by five, while he made breakfast. Those were seldom conventional breakfasts. Sometimes we had steak, sometimes cold leftover venison or duck, sometimes chocolate cake in a bowl with milk poured over it. And there were always fresh oranges or figs, grapefruit or persimmons from the neighborhood trees. Mother would be up by the time we left, grabbing a bowl of cereal and starting to paint. My absence gave her many quiet hours in which to work, while at the stable I learned to clean saddles and to fork hay with a pitchfork small enough for a child. My father was a strict, demanding teacher.Otto Rousseau was a tall, lean man, with sun-leathered skin and arresting blue eyes; a hard-muscled, active man, quiet and charming. But he was an intense man, too, with a quick temper, a man a small child would never dream of disobeying. He was born loving horses. When he was a little boy growing up on their Montana farm, horses were all he talked about. He would stand at his mother's knee making up stories about the horses he would own someday. He left home when he was sixteen, to break colts and herd cattle, That was in 1912, when huge herds of cattle still roamed the western ranges, and when a boy of sixteen was considered a grown man and ready to do a man's work.

He was seldom away from horses again, except when he joined the army as a cook during World War I, and then directly after the war when, for a few years, he ran a bar and grill in Berkeley, with gambling in the back room. It was in a more polite environment, though, that he met my mother, at a college party. She was a student then at California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. They were married in Oakland, and I was born there a year before the 1929 stock market crash. Just after the crash they packed me up and moved to Southern California, where Mother's parents had already settled. The tall brick house was then so new the vines hadn't begun to cover it.

As the depression took hold of the country, so many people were out of work that there were long lines at the public soup kitchens, and men did whatever work they could find. My father painted houses and did plastering and carpentry work. But he found time to train a few horses, too. He rented a barn some miles from our house, in exchange for which he did maintenance on the adjoining farm. It was here that he and Patsy taught me to ride. Patsy went back to her owners just before my fifth birthday. On that birthday morning I felt very lonely.

Hillside Homes, painting by Helen Rousseau, 1960s

Hillside Homes, painting by Helen Rousseau, 1960s

There was no sign of any party preparations, no sweet smell of cake baking, no hint of hidden presents. There was no special dinner planned that I could see. My grandmother was not, as would be expected, busy in her big kitchen. Around midmorning when I was feeling hurt and glum, certain that everyone had forgotten my birthday, my parents bundled me into the car and we headed for the stables.

Standing in the stable yard was a black and white pinto pony. He was brushed and polished, and saddled with a child-sized English saddle. His name was Micky. He would be on loan to me until, at seven, I outgrew him. I climbed on, and off we went, Micky, Sport, and I. We didn't come home until hours later when my father rode out to find us.

The birthday cake came after dinner that night at my grandparent's house, with a few more presents, but no present could compare with Micky. From that day on, he and Sport and I were free to roam where we pleased over the broad countryside between the open fields and small farms. In those days a child was quite safe alone. On horseback I explored the little dirt roads around Seal Beach, trotting through eucalyptus groves and down dry, sandy riverbeds and between broad fields of alfalfa or bean plants. I had only one pressing problem. If nature called, and I had to dismount, I had a hard time getting back on. I could not reach the stirrup and could only mount by leading Micky close to a fence so I could climb. I could get him close to the fence all right, but each time I climbed, he would move away.

I would jump down and move him close again, and climb again. After several tries I would be angry and shouting. Micky had a fine time teasing me. But at last he would allow me to mount, and off we would go. Often, around noon, I would present myself at one of several small neighboring cattle ranches, where I would be given a bite of lunch while Micky rested, and then drank from the water trough.

Our stable was half a mile from the ocean, and sometimes a group would ride bareback out to the sandy beach and take our horses in the surf. It was wonderful to ride through the crashing waves. But I was not allowed to go there alone. In all that wide country there were only three places that were off limits: the main highway, the ocean, and the road that led to these, because this road ran through quicksand. The roadbed was raised and safe, but the quicksand bog lay deep on both sides like a wide brown lake. I knew that quicksand could swallow a horse and a child and I was terrified of that place.

But temptation lay beyond it, where the sea heaved and crashed. I longed to ride Micky there and plunge into the sea.

I might even have braved the quicksand for that treat. But I wouldn't brave my father's anger. I knew that his orders were not arbitrary. They were given for my own safety and for the safety of my horse. Always uppermost in what he taught me was the care and safety of the animals we worked with.

Painting of a horse by Shirley Rousseau Murphy, 1950s

Painting of a horse by Shirley Rousseau Murphy, 1950s

When I was seven we moved our home from the apartment beside my grandparents' house to a rented house that had once been a duplex. Its inner walls had been torn out to make one long living and dining room, but its two front doors remained facing each other across a small, roofed porch. Salesmen would come to one door, then, having been dismissed, would cross the porch and ring the other bell. They were always surprised when the same brown-haired lady answered the second door. My mother didn't remove the second bell or put up a sign; she thought the deception was a great joke.

This house had three bedrooms, so Mother had a studio, and I had a big, sunny room with space for all kinds of projects. My rooms were never done up as a little girl's pretty bedroom. I have never seen the use of a little girl's room that is only pretty, and doesn't offer work tables and shelves and a place to do things. A child's room, if he is lucky enough to have a room of his own, may be his only private place. It should be a place of ideas, a place for a child's kind of work.

My shelves held notebooks of poetry I had written, and dozens of house plans that I drew. I loved to design houses. There was a drawing pad filled with fish pictures that I did after reading The Water Babies. A row of glass jars housed caterpillar cocoons waiting to turn into butterflies, and in a cage lived my two white mice. In a glass terrarium lived a succession of horned toads that my mother and I caught in sandy vacant lots. Horned toads will hold very still as you stroke them and will let you pick them up. I kept each for a few days, fed it dead flies, then turned it loose.

On my bookshelves were Raggedy Ann and Andy, The Wizard of Oz, East o' the Sun and West o' the Moon,and many fairy tales. Best of all was my battered copy of Alice in Wonderland, which I read so often that I memorized every poem and would happily recite them.

When I entered first grade I was already reading, and my first reader was a terrible disappointment. I had expected an exciting book that would carry me away as did my books at home. Instead, we had Dick and Jane. I had to repeat over and over, "See Spot run. Run Spot run," until I went home crying with frustration. That experience nearly ended my natural eagerness to learn. I would sit in school listening to endless repetitions of "See Dick run. Run Spot run" until I was nearly out of my mind with boredom and longed only for the end of the wasted day when I could hurry home, where I could curl up by the window and read what I considered a real book.

I loved Freddy the Detective, and, though wouldn't play with girl dolls, I had a pig doll that I named Freddie. When I outgrew the Freddy books-- though I have never outgrown Alice--I read the Tom Swift books, all of the Tarzan series, and later, Zane Grey and every western writer and horse story I could find. My grandmother bought me the Greek myths, and of course I loved Pegasus best. Among the children's plays we saw together I remember clearly The Bluebird, its sense of otherness, that same sense of mysteriousness that made me love The Water Babies and then Pegasus, and which led me, years later, to C. S. Lewis and Tolkien.

And then there were the books in my grandparents' house; I spent hours sitting on the rug in the upstairs hall beside the tall, glass-fronted bookshelves. These were adult classics, and I didn't read but sampled them. I was drawn to various passages, to certain combinations of words that set me dreaming. Then on those shelves I discovered Edgar Allan Poe, and I read all of his astonishing stories. These, too, were filled with a sense of otherness, a chill-making melange more gripping and more darkly colored than any modern horror movie.

In those shelves, too, I discovered my grandfather's geology books. Their detailed drawings of the cross sections of rock and earth formations fascinated me. Many years later, those intricate renderings would influence my abstract paintings, just as Poe's rich, surprising stories would help guide me toward writing fantasy.

With friend Nancy Skull, Long Beach, California, 1936

With friend Nancy Skull, Long Beach, California, 1936

Strange how those impressions that I collected when I was small became a part of my personal wealth, gifts of meaning to my grown-up self. Thus do all children collect, with the same intent hunger. That is a child's work, to salt away into his personal time machine, impressions and ideas to be harvested and built upon in the far future.

Though what we collect is not always treasure. Ideas and impressions can also destroy. The negative, sick images we might collect, if they are overpowering, can make us self-destruct.

The letters I get from young readers sometimes show me a person lost in a world that seems to have turned on them. But perhaps sometimes it is not the world at all that has turned, but those inner images. Maybe, when the world seems to have sabotaged us, it is only the powerful inner passions of childhood that have been twisted, that have not found their way to building a spirited, positive self.

I had one close friend during those early years, until her father, who was a navy captain, was transferred and they moved away. Our families had known each other long before we were born. Nancy and I looked so much alike, with our pale hair, that we were often taken for sisters. We rode together, there was always a horse for Nancy, and we went to Saturday matinees, double features with a western serial. We swam in the ocean and came home sunburned and sandy, and we played countless games of Monopoly in which we ended up fighting and didn't speak the rest of the day. Nancy was Catholic, and for a while I attended mass with her. I found the intricate and beautiful Latin rituals amazing and intriguing. My parents didn't go to church though they were not atheist, and they taught me strong Christian ethics. I never did join a church. My lack of a formal religion left me with a determination to find, through observation and reason, my own answers.

*

As the depression eased its hold on the country, and the economy began to revive, my father's horse-training clients increased. By the time I was twelve, he was training horses for many people. He boarded pleasure horses, broke colts, and showed stock horses, polo ponies, and jumping horses. Sometimes he furnished horses for the new and growing movie industry. He provided the jumping horse for The Bride Wore Boots, and he supplied all the "extra" white pasture horses for the movie Florian. These are old movies now, from a time so long ago that Dan Dailey was a young new star whom my father taught to ride.I rode our boarded horses to keep them exercised, and I rode our green, broke colts when they wouldn't buck anymore, helping to put a nice rein on them. Each colt was ridden in a hackamore for many months before he had a bit in his mouth. Riding the colts was demanding, and there was no time to daydream. I was learning right along with the colts, and I felt secure in my father's steady discipline.

Discipline doesn't mean just punishment, as we sometimes think. It means to develop your own control, as an athlete develops control, to shape your own powers and direct them.

*

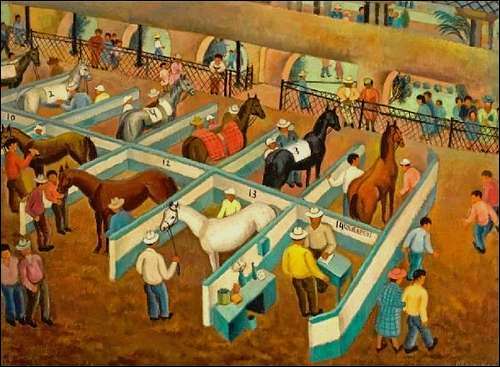

Saddling Paddock, painting by Helen Rousseau,

Caliente Racetrack, Tijuana, Mexico, 1947

Saddling Paddock, painting by Helen Rousseau,

Caliente Racetrack, Tijuana, Mexico, 1947

Nearby was a ranch that had been planted with every kind of tree and bush that would grow in California. This wide, tangled arboretum marched in a square around an open field, and it was a wonderland to ride through, among so many shapes and colors of leaves, berries, and flowering trees. The smells were of sharp eucalyptus and tangy pepper trees, and I liked to chew on the pepper berries. On early mornings I made a game of galloping my horse under the trees, ducking dew-covered spider webs strung between branches. If I hit a web, I would have a live passenger in my hair, so I was very quick.

On hot days, if the irrigation ditches were full of rain water, I could take my horse in to splash and cool off. But once when the ditches were full from heavy rains, I forced my horse in against his better judgement. We had quite a battle, until at last he slid down the muddy bank. The water was over his head, and the current was fast. Too late I realized what I had done. The sides of the ditch were too tall and slick for him to climb out again with me on his back. I slid off and climbed up the muddy side ahead of him, and pulled with all my might to get him out. This was the only time I can remember doing such a foolish thing to an animal. I never told my father and was quiet and obedient for a long time afterward.

The days I spent with my mother were quite different from life at the stables. She took me to art exhibits, so I knew the bright, innovative work of other California artists. I also went sketching with her. We'd pack a lunch and drive down the coast between the golden hills and along the sea cliffs. Although she was fun to be with, her one fault made me cross. She could never bring herself to give me a direct order; she did not have my father's strong, decisive ways. She would make a gentle suggestion, when I would rather just have been told. I was a difficult, headstrong child, and I needed a strong hand. Being told what to do, briefly and clearly and with authority, made me feel secure. My mother's hesitancy in this respect left me uncertain and often enraged. I described that feeling years later when I wrote Poor Jenny, Bright as a Penny, when Jenny says, "You need something to push against . . . Maybe that's what being told no is, a kind of wall you push against. You keep pushing, but you really want it to stay steady. Otherwise there's just emptiness. Nothing to hold you."

My mother took very good care of me and she loved me, but she could not provide that kind of strength.

*

Every summer my grandmother took me and my cousin Bob to the mountains for two weeks to a rented cabin where we carried our drinking and washing water in a bucket from the stream. We hiked, and there were sing-alongs around a campfire at night. Later they built a cabin at Lake Arrowhead, with one big dormitory upstairs. My grandfather loved to get up at three in the morning and go catfishing. Catfish are ugly things, with wide grins in their slick, dark faces, and long, stinging whiskers hanging down.By the time I got up and came downstairs he would be home again, and the kitchen smelled powerfully of catfish. Fish would be piled so high in the kitchen sink and in the laundry sink that they were sliding over the edge. There would be catfish frying on the stove, and when I opened the refrigerator, I saw nothing for breakfast, only rows of catfish grinning out at me, He was always amused that I wouldn't eat on those mornings.

When I was nine we moved to another rented house, and a year later my parents built the first house they had ever owned. Now my mother had a bigger studio, and a big vegetable garden, too. She made wonderful vegetable soup, which we had with fresh baked bread from the local bakery. There were orange trees in that yard, and a huge fig tree where I could sit hidden among the branches eating all the fresh figs I wanted. That same year, my father built a new stable two miles from the old one, again on rented land. I had long ago outgrown my little pinto, Micky. He had gone to live with another child, and though I rode many horses, I didn't have a horse of my own until I was twelve.

Jeff, Long Beach, California, 1940

Jeff, Long Beach, California, 1940

I had been, for several months, riding the horse of a family friend, a bay mustang gelding. He was a barrel-racing horse. He was stubborn, hardheaded, and he loved to pull tricks on me. I spent considerable energy trying to outsmart him. He was thirteen hands high and had a white face and one white eye which gave him a devilish look. He was fifteen years old, three years older than I, and far wiser. He knew every trick a horse can know to harass a young rider.

When, on hot days, Jeff would walk along dozing, I would throw a leg over the pommel of my saddle and ride along with both legs on one side. I would be half-asleep too. But suddenly I would find myself standing on the ground staring stupidly at Jeff. He had slid out from under me, quick as lighting, and left me standing. And as I stared at him, he would twitch his ears with amusement.

Jeff was perfectly safe, he would never buck, and he didn't shy easily. But I couldn't tie him up with a bridle, he would pull back and break it. When I put him in a barrel race, he wouldn't leap forward at the start with the other horses, he would run backward, round and round the arena, completely embarrassing me.

Otherwise, we got along very well. And on my twelfth birthday, Jeff's owner surprised me with a card tied to Jeff's tail. Jeff was to be my pony; he was my birthday present. I have never again had such a wonderful gift as that hard-headed, clever pony. And even though he was quite safe in most ways, he nearly killed me. What happened was truly my fault.

I couldn't ride Jeff anywhere in a halter. Without a bit in his mouth, he would run away with me. The only way I could stop him was to slide off before he was running too fast, and pull him to a stop.

There was an ice-cream truck that, each noon, would park near our stables. On one very hot day I wanted an ice-cream cone, but I was too lazy to walk the block to the truck. Jeff was tied to the fence with a halter. I got on bareback, thinking surely he couldn't run away with me in that short distance if I kept a tight rein on the halter rope.

I made it to the truck all right and bought two cones, one for our stable boy. I was on my way back, holding a cone in each hand, with the halter rope tucked under my elbow, when Jeff broke into a sudden, dead run.

Our stable was built with stalls in two long rows flanking a covered alleyway. At that moment, tied in the alleyway was a new, skittish stallion. He stood in the center of the alley, with a taut rope extended from each side of his halter to the wall. He was edgy and nervous. When Jeff took off running for the barn, the only way I could stop him was to slide off and pull him down. I couldn't get off without dropping the ice-cream cones so I stayed aboard, trying to figure out what to do, and hoping for the best as Jeff sped for the alleyway.

The stallion eyed us, rearing and kicking, his tie ropes strung tight as wire just at the level of my throat.

Jeff burst into the stable, speeding past the stallion. At the last instant I ducked to avoid breaking my neck against the ropes. The stallion went wild, bucking and kicking. Jeff stopped at the back of the barn. I hadn't spilled the ice-cream cones.

Cover of the Viking edition of The Sand Ponies

Cover of the Viking edition of The Sand Ponies

My father grounded me for a month. I was not allowed to come to the stables, a whole month of my summer vacation destroyed. Luckily, the stallion didn't hurt himself, and neither did Jeff. But I was ashamed and embarrassed to have done such a stupid thing. And not only had I gotten myself in trouble, but Jeff was in disgrace, too. Though that pony was often in disgrace.

Jeff could get out of any pasture, but he did that only at night, slipping between the strands of barbed wire so cleverly that the wire stretched but didn't cut him. When he escaped, he took other horses with him. His little band of horses would head across the busy city through heavy traffic, toward the distant Los Angeles stockyards. It was there that Jeff had arrived in California, by train, a little colt beside his mother. She had been a wild, captured mustang, shipped from Arizona to be sold in California.

Each spring, as the new grass sprang up green and fragrant, Jeff's need to go home must have been powerful, for he would break through the fence and head for L.A., and he was never alone. Having horses loose in a city is a terrible thing and far worse at night when drivers can't see them. One very good mare was killed by a car because of Jeff's escapade. My father would have gotten rid of him, except that I loved him.

Jeff lived to be twenty-eight. Years after his death, when I began to write books for young readers, he was the pony in my first two books. In White Ghost Summer, he is Buttons, who pulls the same tricks on Mel that Jeff pulled on me. And in The Sand Ponies, he is Kippy, who leaves his pasture by slipping through the fence and takes the other horses with him, heading back to his colthood pasture.

*

Shortly after I got Jeff, we moved stable again, back to the one with the racetrack, and I rode with a new friend, Ruthie, who also had a mustang, a little grey gelding. When she and I had an argument, we settled it by racing our ponies around the quarter-mile-track. When we moved stable again, to nearby rented land, Ruthie still rode with me, and we made a jump course out of brush and broken tree limbs. But neither pony would jump anything: all they did was crash through.My father watched for a while as we repeatedly tore up and rebuilt our jump course. Then he had me start riding the real jumpers. Soon I was riding in some of the smaller shows, and the easier classes in the big, ten-day horse shows up and down the California coast. One of the nicest horses to ride was our big Thoroughbred stallion, El Rambler, who was steady and reliable. The main thing I had to do on Rambler was leave him alone, keep a steady seat, and not disturb or unbalance him.

I would get out of school in the fall for several weeks to go to the horse shows. We stayed in hotels near the show grounds in San Diego, Pomona, or Santa Barbara. To ride in open classes against adults is a daunting challenge. It is the horse who wins, not the rider; the rider can give a good ride, and help his horse win, or he can give a bad ride and ruin everything. I guess I did some of both.

Riding El Rambler, Santa Barbara Horse Show, 1941

Riding El Rambler, Santa Barbara Horse Show, 1941

School during those years was all right, but most of it wasn't challenging. I was always an outsider in school. I didn't mix well with children my age. Our interests were too different. I loved English and worked hard in that class. We didn't have history, for which I've always been sorry. It was algebra where I failed dismally.

I started out well enough, and even liked algebra. But then I was sick for two months, the class got ahead of me, and I didn't ever catch up. No one thought to find a tutor, and Mother let me drop out. Without algebra and the math that follows, I had no hope of becoming an architect.

I convinced myself I didn't like math, abandoned all thought of architecture, and decided to be an artist. No one suggested that I couldn't make a living in the arts. Anyway, in those days girls expected to get married and let the man make the living. Since that time, professions in the arts have grown even less reliable as ways to support oneself. I had no notion that I was ignoring a lot of the options. I was intensely hungry for so many things: to paint, to build houses, to write. Yet most of that energy went undirected; I didn't know quite what to do with it. Then, when I was thirteen, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, and life changed drastically for everyone. The United States was at war.

*

Our stable boy Billy was called up and killed in the Pacific. The next years held suffering for millions of our servicemen and their families. Our own family was more fortunate. We lost no one close to us. The war changed my life in far less violent ways, though they were changes that directed my future.My father closed the stables and sent the boarders back to their owners. He sold some of our own horses and turned the rest out to pasture. Jeff was turned to pasture, and I didn't ride anymore. My father was absent for months at a time, driving earth-moving equipment, building roads for the army. He had served in World War I, so he was not called back for uniformed duty. I was home with my mother, without the security of my father's strong hand, and I went a bit wild. I dated whom I pleased, and though Mother trusted me to be sensible, that is not always easy when you're young. When I was sixteen I ran away and got married.

That marriage lasted five years. When it ended, everyone was relieved. But just before I got married, one positive thing happened. I have wished many times that, instead of marrying, I had followed where my life could have led.

*

Shirley's parents, Otto and Helen Rousseau, Whittier,

California, 1951

Shirley's parents, Otto and Helen Rousseau, Whittier,

California, 1951

Until that class, I believed that all one needed to do to write a school paper was copy passages from several encyclopedias. No one had taught me any different. Looking back, it's hard to believe that I had learned so little up until then about how to find and use information. Of course, my school years occurred long before computers were invented`.

Miss Hanson taught us how to use the card catalog and the library's reference tools efficiently, how to take notes on 3" x 5" cards using a brief, formal outline, and how to correctly outline a paper. When we had completed her class, at the end of our first semester in high school, we were able to research, write, and present in correct form a term paper or thesis that would be acceptable in a university, complete with proper footnotes.

Miss Hanson taught us by showing us only once. She made sure we understood her directions, then she sent us to the library to put them into practice. Once we began to research a paper, we were not required to come to class. She trusted us to spend the two hours in the library doing research, and we did.

The research techniques were the English part of the course. The history part gave us the subjects for our papers. Each Monday, sitting around the conference table, she would present to us several possibilities for research, all based on some aspect of American history. We would discuss these, and each of us would choose a subject which interested us. Then we were off to the library, though Miss Hanson was always there in the classroom if we needed help.

We worked furiously for her, and our papers were the proof of our diligence. That class changed, for me, the whole idea of school, information retrieval, and what I could accomplish. It made me wish I had taken such a class in elementary school, that I had known years earlier these efficient keys to gathering information and organizing and getting across my own thoughts.

Before that class was finished, I was married. Miss Hanson tried to talk me into waiting and going on to college. I wouldn't listen. I had little idea then what I was throwing away, nor had I any idea that to build a successful marriage a couple must have a mutual philosophy, and some solid mutual respect and commitment.

But during those five years I finished high school and enrolled at California School of Fine Arts where my mother had studied before I was born. I also learned to cook, to make pies and cakes from scratch, make yeast bread, can peaches, make jam, and to iron starched white shirts. I have never since been so domestic.

*

In San Francisco, before I graduated from art school, the marriage ended. I moved into a boardinghouse and went on with school. After graduation I married again, a very different and wonderful man, Pat Murphy. He had been a Marine in the Pacific and was one of the first men to go into Japan after the atomic bomb was dropped at Nagasaki. When he got out of the Marines he worked as a welder in the Navy shipyards, but he was determined to go to college. He would be the first one in his family to do so. We moved to Los Angeles, and I went to work in a commercial art studio while Pat attended the University of Southern California under the GI Bill.

With husband Pat Murphy, Portland, Oregon, 1970

With husband Pat Murphy, Portland, Oregon, 1970

During the next four years I worked at a variety of menial commercial art jobs and then as an interior designer for a downtown department store. We didn't have much money--most married students attending on the GI Bill were poor--but it was a good, productive time.

When Pat graduated and took a position as a United States probation officer in San Bernardino, I quit work. We bought a house in San Bernardino, and I began to paint full-time. I bought acetylene welding equipment, too, and Pat taught me to weld. We fenced in the carport to provide a work area, and I started doing metal sculpture. And now that I was exhibiting, I took Mother's work along with mine to enter in the juried California shows. It was a day of celebration when our work was selected for an important show, and a day of delirium when one of us won an award.

Then, in 1962, Pat transferred to San Francisco, and we moved to the small village of Mill Valley, north of the Golden Gate Bridge. My father's current jumping horse rider lived in the Bay Area, so it was convenient for my parents to move as well. My father resituated his training operation, they bought a house near us, and both families did some remodeling. Our house was tiny, with a walled front garden, so we turned the living room into a bedroom and built a new living room looking out the back among giant redwood trees, with a studio underneath. Pat and I have never owned a house we didn't change; I guess it's my frustrated longing to be an architect. But then, I have also had a dream of being a trumpet player and a jazz singer, and that hasn't led anywhere except to collect jazz records.

Mill Valley was small. We could walk through the woods to the village for dinner or for Sunday breakfast. Thirty years later it would become the setting for The Catswold Portal. We soon bought an old shack, too, and remodeled it into a nice rental house, doing the work ourselves with the help of Pat's parents, who lived across the bay. Just as we finished that house and found our first tenant, we moved again, and this time we left the continental United States.

Late in 1963 Pat was asked to establish the first federal probation office in the Panama Canal Zone, so we packed up. But just a few weeks before we were to leave, my father died suddenly. He had not been ill, and he had still worked eight and ten hours a day training and showing jumping horses. His death was a terrible shock. He had in his last years trained three riders for the Olympic teams, and his phenomenal horse Calico Cat was a contender as an Olympic jumper. After Cat was injured in a heartbreaking accident, my father had not put him down but nursed him along like a baby.

Shortly after my father's funeral, we left for the Canal Zone and took my mother with us. There she continued to paint, and she produced a powerful series of Panama street scenes. We did a lot of sketching around the public market where farmers brought their garden produce, and the harbor where fishermen in little crowded boats brought in their catch to sell. I painted for a while, but then I stopped and began to write.

There were few juried exhibits in Central America, and my paintings and sculpture were too heavy to ship back to the States for shows. Mother was content to amass work against the day she would return home, but I wasn't. We did have the honor of being the first two North Americans to exhibit in a two-woman show at the Instituto Panameno de Arte. But after that, there were no other nearby juried exhibits.

Geese on the Lake, painting by Shirley Rousseau Murphy, late 1950s

Geese on the Lake, painting by Shirley Rousseau Murphy, late 1950s

Shortly before the date set for that show, which was to have television coverage and a champagne opening, a small war broke out in Panama. The 1964 riots exploded, beginning with a burned American flag, and accelerating to rifle fire. As rioters burned Panama at the border, American army tanks patrolled the Canal Zone streets to protect U.S. citizens. While Pat was in court, rioters threw Molotov cocktails in through the windows.

My mother was staying in Panama at the time, in an apartment. We got her out at three in the morning, with a handful of other Americans, in a Panamanian police wagon.

We thought that after the riots our exhibit in Panama would surely be cancelled. But it proceeded smoothly, among many Panamanian friends. That was my last exhibit.

*

I had for many years wondered if I could write, and this was a good time to try. I put away my paints and got a job in the Canal Zone library. I worked in the basement, preparing new books with cards and pockets and helping with the library's museum exhibits. Every night I brought books home, making my selections during lunch break under the direction of a fine children's librarian, Alice Turner. She gave me invaluable guidance, and she introduced me to C.S. Lewis's "Narnia" books and to many other children's authors. It was Alice who, during lunch one day, told me something I will never forget. I had mentioned that I found a particular TV program boring. Alice looked at me sternly. "To admit to boredom," she said, "is to admit to intellectual poverty." If you are truly alive and your wits are honed, you can always find something to amuse or enlighten yourself, some twist or detail from which to build experience, pleasure, and ideas.When I had read through much of the children's collection, I bought a typewriter and a stack of cheap paper. We lived just blocks from the library so there was no commute time to account for, and Pat was working long hours. I had many evenings and weekends in which to work.

I knew I wanted to write fantasy, but the two manuscripts I wrote that year were all fluff and no muscle. I didn't know how to make fantasy real, how to combine solid detail and feeling with the soaring elements of fantasy. I had taken no classes in fiction writing, and while that isn't essential, it helps.

After my first fantasy had been rejected half a dozen times, I took another piece of advice from Alice. I started a horse mystery, a subject with a larger demand, and one for which I had some specific experience.

Jeff was perfect for the wily pony, and my grandparents' attic is where Zee Zee builds her model house. The manuscript for While Ghost Summer sold the first time it was submitted. We celebrated when I received the overseas cable from Viking telling me they had accepted it, and the next day I began a second horse mystery. When six months later Viking accepted The Sand Ponies, I was pleased not only for myself but for Jeff, who had appeared in both books. Now other children could share some of his deviltry, and my love for him.

My third published book came from the experience of Miss Hanson's class. The wonder of discovery in that class had never left me, nor had I ever lost that sense of wasted school years because I hadn't learned the skills Miss Hanson made available early on. I wanted to write a story which would open those skills of discovery to elementary school children. And maybe, if I could write such a book, a little of myself could travel back in time to those years and find more satisfaction in them.

The story is set in a library and begins when the young mouse Elmo is insulted by a neighboring cockroach. "It must be very discouraging to be nothing but a mouse."

Enraged at the insult, Elmo decides to research his family roots and prove that a mouse is a noble creature. For Elmo's research I used real books and magazine articles about mice. I found flying mice from Africa, zebra mice, snow mice, and the rare and beautiful golden mouse. Whatever Elmo does in the story, such as inventing a pulley system to lower the heavy books, I did first to be sure it would work. Then, as I was in the middle of writing Elmo Doolan and the Search for the Golden Mouse, we moved again.

Cover of Pat and Shirley Murphy's book Carlos Charles, which was

based on their experiences in the Panama Canal Zone.

Cover of Pat and Shirley Murphy's book Carlos Charles, which was

based on their experiences in the Panama Canal Zone.

Pat felt that his job in the Canal Zone was finished. He had established a smoothly running probation office to serve the U.S. Courts, and we had not planned to stay in Central America forever. We had done some traveling--to the San Bias Islands, the Bahamas, Peru, Colombia, and the Dutch West Indies--and we were ready to come home. Pat accepted a position as a U.S. probation officer in Portland, Oregon.

We bought a house in Portland and added an upper story by jacking up the roof on one side and building new walls under it. Mother had, some months earlier, gone back to the San Francisco Bay Area, where she had an apartment and was painting and exhibiting.

In Portland, during the remodeling, as carpenters pounded, I wrote three complete versions of Elmo Doolan before I had what I wanted. That book was my first published fantasy. My next book was a realistic story based on our experiences in Panama, and Pat and I wrote this one together.

As a probation officer, Pat had spent a lot of time in the Carcel Modello, the Panamanian prison, a crowded and far more primitive institution than American prisons. The story of Carlos Charles begins when twelve-year-old Carlos, a Jamaican street boy without a home, is locked up with hardened, adult criminals. At supper Carlos follows the men into the walled exercise yard where he is handed a rusty tin can. This is filled with fish soup in which float fish heads, bones, and scales. He is also issued a hunk of dry bread. He watches the other prisoners hold the bread over the can to strain out the bones and heads while they drink. Carlos can do the same, or he can go hungry.

Toward the end of Carlos Charles, Carlos stows away on a twin-engine plane which crashes in the jungle. This was based on a real plane crash that occurred while we were in the Canal Zone. The plane went down in the middle of hundreds of miles of jungle swamp. The pilot was killed, and three Canal Zone engineers were seriously injured and rescued by U.S. Army helicopter.

Pat, who has a private pilot's license, and two other pilots decided to salvage the wreck-age. They got the salvage rights from the Panamanian government, then flew over the dense, unbroken jungle. When at last they spotted the wreckage, nearly invisible among the trees, they dropped red balloons tied to rocks to mark the spot as well as to mark a path through the jungle to the deserted seacoast.

Returning to Panama, they left their plane and hired a shrimp-boat captain to take them down the coast on his regular fishing run. It was an all-night trip to the point, where the red balloons shone from the empty jungle shore.

The three men had brought an inflatable life raft, and they left the shrimp boat a mile from shore and paddled through the wide surf, then continued in through the swamp another mile to the crash. On the mud around the wreckage scuttled land crabs that would eat living flesh.

We received many letters from readers about that part of the book, where Carlos, stubborn and resourceful, makes the long, frightening journey through the swamp and across a mile of ocean to get help.

Shirley with her cat Mousse, 1977

Shirley with her cat Mousse, 1977

After Carlos Charles, Poor Jenny followed. Jenny is a gifted child, fighting against great odds to break out of the trap of an unhappy home. Abandoned by her mother, she is in juvenile hall for some time. I visited juvenile hall in Portland to try to get a feel for living there, locked up among girls, some of whom I would pity, some hate, and some whom I would fear. But Jenny is a survivor, and she spoke to me most clearly in her diary, where she records her own uncompromising views of life.

When Poor Jenny was finished we moved again, this time across the United States to Atlanta, where Pat was asked to be chief U.S. probation officer for the northern district of Georgia. We bought a house, immediately moved some walls, and I began The Ring of Fire, the first of five fantasies that would take me four years to write, sandwiched in between several younger reader books, including The Flight of the Fox, which would turn out to be a Junior Literary Guild selection.

I still had my research from Elmo Doolan, including material on lemmings and kangaroo rats. Lemmings are shy little creatures, excitable and quick to panic. By contrast, a kangaroo rat is a tough, cheeky fellow. He can jump six feet straight up in the air, and will kick his enemy in the face or kick sand in his eyes. With these two very different characters, I soon added a model airplane which stood in our basement in Portland, a biplane with a four-foot wing span that Pat had built. Its cockpit was just the right size for the two rodent pilots. Next in the tangle of emerging ideas came the city dump. I had frequented such dumps during my welding days, searching for scrap metal. I began The Flight of the Fox with the wrecked model airplane discarded in a dump. The hobo kangaroo rat finds it and decides to convert it into a plane he can fly. This job requires extensive modifications, and I made sure that each one would really work. I was completely caught up in the story, rising at five, not stopping work until evening when Pat got home.

As a child, when I painted or wrote stories I worked steadily for many hours; I liked long, involved projects. I worked that way as a painter, and now as a writer, eight and ten hours a day, shutting out everything else. As a child I was never discouraged from such solitary projects, and I didn't have TV to distract me. After Elmo Doolan came Silver Woven in My Hair, a collection of Cinderella tales within a Cinderella story. It was while writing this book that our little cat found us.

*

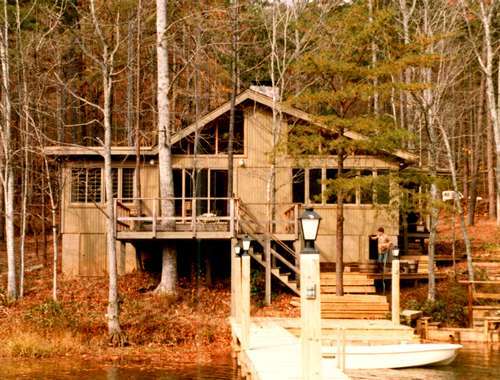

The house on Grandview Lake, Georgia, 1977

The house on Grandview Lake, Georgia, 1977

One morning I looked up from my desk through the front window and saw a little calico cat in our yard. I didn't recognize her; she was not a neighborhood cat. She was young and looked very hungry. I slipped outside and sat down on the porch, remaining still. She soon came to me, flashing her golden eyes and rolling over, all coquettishness and charm as she worked me for a meal. I would learn later that she had been in our neighborhood for many days, going from door to door looking for handouts, always being chased away.

I invited her in the house and fed her, and she never left us. I named her Mousse. Soon she took over my desk, lying on my manuscripts, defying me to work. She was so bright and personable, as charming as a young girl, that I found myself weaving a story around her. That book, some years later, would become The Catswold Portal, my first adult fantasy, in which cats do indeed take human form.

Two years after we moved to Atlanta we discovered a sparsely populated lake in north Georgia, where we bought a lot and built a cabin. Until Pat retired we spent our weekends there, fishing and swimming. Pat had bought a used Cessna 180, a sturdy single-engine plane with conventional landing gear. Sometimes we flew to the lake, and we took Mousse in her cat carrier. She did well in the plane, except that she never did get over the habit of throwing up during takeoff. Once that was accomplished, and cleaned up, she settled down just fine. Two years after Mousse came to us, a beautiful Weimaraner, a silver-colored German pointer, joined our family, a willful, hardheaded, intelligent dog who kept us on our toes trying to outsmart him.

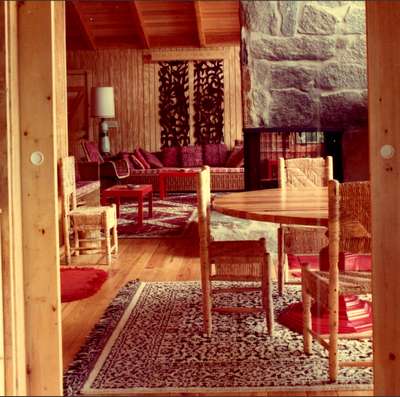

Living room of the lake house, 1980s

Living room of the lake house, 1980s

Jake was, to begin with, so unmannered that he snatched sandwiches from our guests' plates and even from their mouths, and he quickly destroyed the furniture with muddy feet. But he was charming and clever, and we set about training him to become a pleasant companion. We taught him the basic commands of obedience: to come, heel, sit, and stay. But he always let us know if something we required was beneath him. He would do all the commands except "lie down." He refused to do that; it was too subservient.

During the time that we were coming to the cabin on weekends, I was still writing the Ring of Fire quintet, and also did two picture books. Both were stories that bothered me until I got them down on paper. The first one grew from an experience at the lake. During a heavy rain, our lake rose alarmingly. It threatened to wash out the dam, and it pulled up some of the docks by their pilings. A young neighbor asked me what would happen if the water rose higher, and I said I supposed some of the houses might float away. That became the beginning of Tattle's River Journey, in which Tattie's house does float away, taking Tattie and her cow and chickens with it. The other picture book was Pat's story, an idea that was born as, from his office window, he watched the city of Atlanta grow so rapidly it seemed like a new skyscraper was added every day. To make room for new tall buildings, old houses were torn down. In Mrs. Tortino's Return to the Sun, a little old woman refuses to let the builders destroy her home. Her stubborn inventiveness results in a wonderful new life for herself and for her old house.

Shortly after I finished the Ring of Fire quintet, we moved again, this time to the lake. Pat was retiring. Probation and parole work is considered hazardous duty, and at that time an officer was required to retire by age fifty-five. Of course, as soon as we moved we began adding on to the cabin, to give each of us a study and room for company. Our dog Jake helped the carpenters by stealing their jackets and lunches and before the stairs were installed he learned to climb the ladder.

With the Ring of Fire books now behind me, and the moving boxes unpacked, I began the Nightpool trilogy. The sea, and the lakes and marshes of Oregon formed my first inner pictures for the world of Tirror.

*

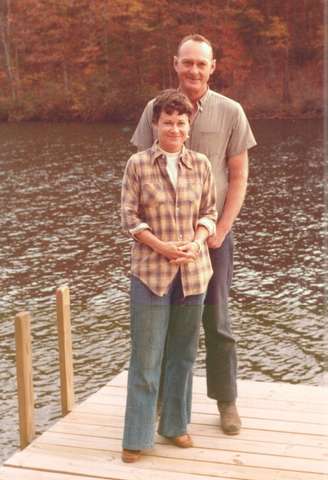

Shirley and Pat on the dock at the lake house, 1977

Shirley and Pat on the dock at the lake house, 1977

When I understood the island world of Tirror, next came the dragons winging across Tirror's skies, and they were creatures of great wisdom. Then soon, otters appeared, idling on the ocean waves, argumentative, cheeky, tool-using animals. Next came the speaking foxes, a short-tempered owl, and later the great cats and the wolves. All are speaking creatures, and each group has a culture of its own, yet all are important together to Tirror's strength and freedom. And the question in my thoughts was: What would this world be like if those who lived here had forgotten their past--if they, like amnesiacs, had no memory of their history?

Tirror has no written history--the singing dragons are the keepers of the world's past. Through their song they call forth telepathic scenes of times gone. But as the story of Nightpool begins, the dragons have vanished from Tirror. No dragon sings his image-making songs, and without the knowledge of their past, people have forgotten who they are. They are adrift, without roots, weak and crippled, and they have been easily enslaved. But then it is found that two dragons have remained, and soon a clutch of young new dragons appears. Then the dragonbards, the special humans who can join with their young dragons to bring alive once more visions of Tirror's heritage, come forth. Nightpool holds for me the places and dreams of my childhood. This gathering in of thoughts and experiences, so as to shape them into something new, is universal to mankind. Each of us uses this strength in a different way. But it is a power that belongs to all, and it is a part of our unique human magic.

What books my future holds, I can only guess. I know I will write as long as I am able. A writer doesn't retire. Writing is not a profession so much as an addiction. Only through writing can I see the world truly, and try to make sense of life's tangles.

*

Update, 2016 - From Dragons to Cats: The Following Years

Pat Murphy's Cessna 180 on his trip to Alaska, 1995

Pat Murphy's Cessna 180 on his trip to Alaska, 1995

Now that we lived at the lake full time, the temptation to leave my work on Nightpool and step out the door to swim, usually with Jake, too often drew me away. So many things to do: work in the large vegetable garden I had planted, help Pat cut wood for the winter, run the boat while he fished, enjoy picnics as we drifted down the lake on the raft Pat had built. All shortened my writing time. And of course there were our long walks with Jake every day. But always the three books of the Dragonbards Trilogy would pull me back again into story, draw me back to the computer.

Pat flew his Cessna 180 a lot during those years. He met small-plane pilots at the local airport. They hung out in typical southern rocking chairs on the wide front porch of the airport office and talked flying; they went to nearby air shows, camping out beneath the wings of their planes. Pat's flying time was my writing time. It was a good arrangement and a good life for both of us. How could we help but enjoy our new world among the woods and lakes? When I rose at five to swim I would often see a family of otters playing in the lake, rolling and diving. On "otter mornings" I would skip my swim so not to chase them away. I would sip my coffee, watching them, and think about the speaking otters in Nightpool, just as clowning and full of fun. Of course the Nightpool otters can speak, and with the help of abandoned and wounded young Prince Tebriel they learn to use many more tools than our California sea otters did, more than just a stone to break open shellfish. With Tebriel's help they are learning human ways though not all the otter clan approve of that. Now, watching our Georgia lake otters play, I felt as one with them, and with my fictional otters' happy spirits.

Another break in my work that we both enjoyed were the weekends the cabin was full of company, new friends from the Atlanta office, old friends from California, Oregon, half a dozen states. And every summer we had a "girls' weekend" with Pat's chief clerk, all the secretaries and the two female probation officers. Everyone brought food, we swam, walked through the woods, played poker. They slept all over the house, the three guest rooms, our studies, even the garage, which, when prepared for guests, would sleep eight on plywood cots with foam mattresses. And everyone enjoyed our final addition to the cabin, a thirty foot sunroom looking down on the lake. That was great party space--until the tornado hit.

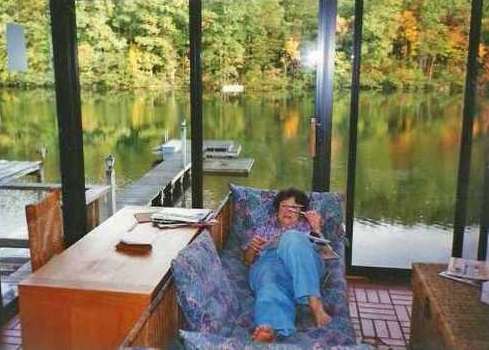

Shirley in the sunroom at the lake house, mid-1980s

Shirley in the sunroom at the lake house, mid-1980s

We had no company that weekend. And we had no warning. It was not tornado weather, just a bit sullen and windy. Pat and I were reading on the couch, with Mousse on my lap, when suddenly a howling wind rattled the windows. We jumped up. I tossed Mousse into a windowless bathroom to keep her safe. The tornado roared straight down the lake between the rising hills. All in a second we watched it lift the roof off the sunroom, toss it into the lake, and send most of the glass panels crashing to the floor.

We rebuilt the sunroom, but it took a long time to clean up the mess and dispose of that huge, thick Styrofoam roof afloat in the water. Before the rebuilding began, we were off to California for our yearly trip home, to stay with Pat's parents, near Oakland, and then to stay with my mother: at first in Sausalito where she had an apartment near a melange of fishing boats, houseboat dwellers, hillside cottages--settings to fascinate any artist. She painted long hours, and she exhibited in all the juried shows, San Francisco Museum of Art, the deYoung, the Marin Society of Artists and many others. She continued to paint and exhibit when she moved to Santa Barbara later to be near her twin sister and her husband. Dimitri had been a Russian Cossack during the First World War, then had flown with the British Air Force. He and Mabel met in New York where she was teaching art classes. They married, and soon moved to Santa Barbara. They both painted, but only occasionally, never with Mother's drive and commitment.

In Santa Barbara Mother found a house a few blocks from them. She remained there after Dimitri died, each sister in her own home. They did not want to move in together: our family tends to be loners, as was my grandfather. This arrangement lasted until my aunt broke her hip and had to be in a care facility. By then, Mother was beginning to fail. The companion we had hired for her was a great help, and she ran errands for my confined aunt, as well. As Mother grew less active, we bought a four-bedroom house large enough to accommodate the companion, and her son and daughter and their two little girls. We remodeled the garage into a large bedroom for the couple, so there was a room each for Mother and Mabel, and they all settled in very well. Of course we still made our yearly trips. And now, during each return to California, I was seeing more strongly the setting for my next book, once I'd finished the three books of the Dragonbards trilogy.

I had thought for a long time about a fantasy set in a netherworld deep beneath the streets of San Francisco, its characters spilling up into San Francisco itself. I knew that calico Mousse would be the lovely, shape shifting young girl. I had had that vision in my mind ever since she came to us, a stray, while we were still living in Atlanta. There was something other-worldly about the little cat who looked at me so intelligently and with such curiosity.

Shirley and Pat at the lake house with their kayak, 1977

Shirley and Pat at the lake house with their kayak, 1977

As I envisioned that world and its heroine, but long before I began to write the first draft, Mousse passed away. She died of megacolon, for which our one veterinarian in the small town did little to help her. It was a disease I knew nothing about, and didn't realize she had, as she was an indoor-outdoor cat who could not be so easily monitored. By the time I knew something was wrong and took her to the vet, he was no help; in fact, he gave me the wrong instructions. She died that night, in my arms, on our long, fast drive to an emergency clinic. Her death was such a painful time for us. But little Mousse's spirit remained with me strongly: I could not stop thinking of the book I would write about her.

I already knew that her name, as a beautiful young girl with many-colored hair, would be Melissa--a girl who could shape-shift into the form of a beautiful calico cat. The fantasy grew around her without my bidding, her story and the visions I saw became ever more real--but I was not yet ready to write. I was making notes, dreaming dreams, exploring the several connections between the two worlds: the tunnel that led from an underground parking garage near Coit Tower steeply down through a warren of earthen and stone passages to the many small kingdoms of the netherworld. The fiery hell-pit where mythical beasts lingered. The lamia, part dragon, part woman, rearing up out of the flames to grab Melissa.

But first, another book intruded. There came the Christmas when a surprising gift exploded into an idea I had to write at once, before I began The Catswold Portal. We cut our own Christmas tree that year, from our woods. We put on the stand, brought it in the house--smelling fresh and wonderful--only to step back, surprised, as a branch moved sharply. And moved again. And out from the center of the tree, along the branch, crept a little deer mouse, very pretty, very confused that his home had been shaken and jostled and relocated. He was so shocked in fact, so disoriented, that Pat, moving quickly, captured him, cupping him between his hands. We took him far up the hill behind our cabin, turned him loose among the trees where we hoped no cats would find him. That experience turned very quickly into The Song of the Christmas Mouse, which seemed almost to write itself.

*

The Murphys' dog Jake with a house guest, 1970s

The Murphys' dog Jake with a house guest, 1970s

Not long after Jake died, while I was, despite my grief, beginning to write a rough first draft for The Catswold Portal, Pat rescued two starving, abandoned puppies. Though only a few months old, they were huge. They were part Great Dane, part boxer. They did not take our minds off Jake; but we raised them, bathed them daily for ringworm, taught them some manners and found homes for both. They had hardly left us when Pat went back to work.

It was nearly ten years after he retired that the chief federal judge in Atlanta called him: The judges wanted him to return to his old position as chief U.S. probation officer, on an interim basis, to put the office in top shape until they found a new chief. This was an unprecedented request; I had never heard of a retired chief being called back to duty.

It seemed strange to be without any animals in our family as we moved into an apartment in Atlanta for three months. We took only minimal furniture, a folding bed, my small desk and computer, a lightweight breakfast table and a few pieces of wicker living room furniture, moving it all in a rented truck. During that time, the spirit of Mousse was so close, weaving with increasing urgency into story.

In Atlanta I worked long hours on the first draft of The Catswold Portal, as Pat worked long hours at the federal courthouse. Our apartment was within a block of an upscale Atlanta shopping mall, yet I hardly ever shopped or took myself out to lunch. So many bright temptations. But the book held me too strongly. Out to dinner, yes, when Pat got home at night. It was nice to be near our favorite Atlanta restaurants; that was a special treat.

Those three months were productive for both of us. We went back to the lake many weekends, but those short trips were not the same. When Pat's tour of duty was finished, we were glad to be home for good. The weather was now warm enough so we could swim, and we had picnics on the raft. When we were out on the lake we missed Jake very much. He had had a small landing platform attached to the raft so he could get down into the lake and climb back out again to nose at our early supper. Now sometimes, when we swam, it was almost as if he were there in the cool water with us.

Lucy after becoming part of the family, 1990s

Lucy after becoming part of the family, 1990s

It was when we were home again that I polished and sent off The Catswold Portal: the lovely young Melissa; a villain queen who is active and cruel in both worlds; and a handsome artist whose life is woven in from the beginning, in a surprising connection to Melissa's upperworld childhood that she, for many years held captive in the netherworld, does not remember. My years in art school colored many of the scenes, as did the vibrancy of Mother's paintings.

Shortly before my agent sold The Catswold Portal, the local volunteer rescue group asked us to foster a little thin cat while her caretaker went on vacation. Black and white Lucy had lived, with her litter of kittens, behind the local grocery surviving on garbage and by hunting. The rescue group had trapped her, and had found the kittens and later found homes for them. Lucy couldn't have weighed four pounds when we took her. At first we gave her a room to herself, a small, secure space with a folding bed high enough that she could hide underneath and I could crawl under, too. Many days when she wouldn't come out I would join her. I would lie under the bed, take her in my arms and hold her tight for a long time. That always eased and calmed her. Soon she was coming out, wanting to explore the rest of the house. From then on she made good progress, gained weight, and was soon secure enough to go outside. For such a little frail cat she was a wicked hunter; she caught mice, rats. She even brought in rabbits--she had changed from a stray or feral cat to a sleek, purring part of the family.

About the time The Catswold Portal was published, Mother's caretaker called me. Mother had died in the night, of congestive heart failure. Her caretaker planned the simple funeral. We flew out, we did all the last painful things that a death demands, and all the paperwork. We put the house on the market, though we were uncertain whether to keep it, return to California, and move in. As we grew older, we both had an urge to move back home to the West Coast where we were raised, we just weren't sure when or where. And then, too quickly to decide, the Santa Barbara house sold. We flew back to Georgia leaving Mother's paintings safe in the locker. We did not return to California for three years. During that time, I began the Joe Grey mysteries. I already knew the cat detective I would write about: I knew him well.

The original Joe Grey in Washington, DC, 1980s

The original Joe Grey in Washington, DC, 1980s

Years earlier, when we had still lived in Atlanta--shortly after Mousse found her home with us--a skinny, half-grown kitten appeared in the neighborhood. He soon was pushing in through Mousse's cat door and eating all her food. She wasn't pleased but she was too gentle to fight him. He was a big, bold kitten, a charcoal gray tomcat with a white strip down his nose, a bit of white on his chest, white paws. He belonged to some neighbors whose daughter had picked him up on the highway. The family had five big dogs, whom they fed on the garage floor. They fed the kitten there, too. You can imagine how much he got to eat. It didn't take him long, investigating the neighborhood, to smell cat food and find Mousse's cat door. After that, he was in and out of our house at his pleasure; he took all his meals with us. But Mousse began to sulk seriously, though we gave her lots of extra attention. Then one day the gray kitten showed up with a broken and infected tail.

We took him to the vet at once, since we were sure the neighbors wouldn't. We had the tail amputated at the break, leaving a two-inch stub, and the infection was treated. It was later that we told the neighbors, and asked if we could keep him. They said we could, with pleasure. We named him Joe. We hoped Mousse would accept him and they would be friends but she never did. We couldn't bear to see her hurting as her home was taken over. Pat talked to a friend in Washington, DC, an animal lover who fed the neighborhood cats and had a young golden retriever of his own. Roger said he'd love to have Joe, and as Pat was ready to fly to DC for a conference, he took Joe with him, in the pet section of the commercial flight. Joe arrived frightened but in good shape; and at the apartment, dog and cat hit it off at once--so much so that, the first day the two men left them alone and headed for the probation office, they were not worried at all that Newton and Joe would fight. Quite the opposite. They returned home that night to find the box of bagels they had left atop the refrigerator now on the kitchen floor, empty. Only crumbs remaining. The next day, Roger shut a new box of doughnuts in a high cupboard. When they got home that box, too, was on the floor, empty, the cupboard door hanging open. Already Joe and Newton had established a cooperative working arrangement.

With this bold, nervy tomcat clearly in mind, I started the first of the Joe Grey mysteries, Cat on the Edge. I knew, after our trips up and down the coast, that wherever we decided to live, these books would be set in Carmel, a picturesque California village at the edge of the sea. I renamed the setting Molena Point. I didn't want to stick to a map or to precise locations; Carmel was simply the prototype. Molena Point has Carmel's charm, but has its own unique elements. Its cozy cottages and bright gardens are much the same, as are the little courtyards set among the small shops, hidden retreats with decorative benches and potted flowers. And of course, all over the village, the spreading oaks and cypress trees that reach from shop to shop and give Joe Grey and his pals sky-high passage, well above the street traffic.

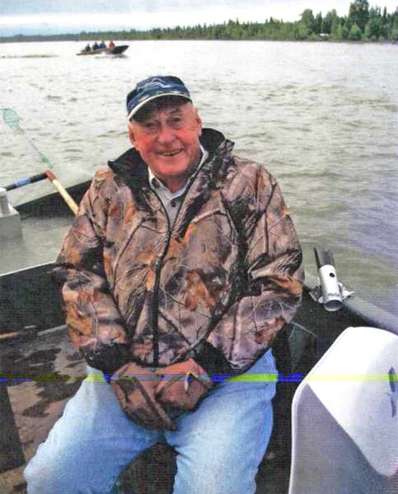

Pat Murphy fishing in Alaska, 2006

Pat Murphy fishing in Alaska, 2006

It was three years after Mother died that we bought a small, old house in Carmel, but three years more until we sold our lake house. When we had added on, it had grown too big for an average family. It sold finally to a couple with five children; it was just what they wanted. During the three years while we had the house on the market, Pat flew the Cessna 180 to Alaska with a pilot friend, camping out at night under the wing. Pat's brother, who was gone by then, had been a bush pilot for many years, and had a grown son who owned a fishing lodge north of Anchorage. They had a good visit and lots of salmon fishing. There was not room or weight allowance in Pat's plane for a third person, and I, not being a pilot, would have been of little use in an emergency.

Shortly after Pat returned from Alaska, another small, abandoned cat demanded our attention--a nervy youngster who soon pushed her way, boldly, not only into our lives but into the "Joe Grey" books. Pat had been flying. He returned at night to the cold, windy, and deserted airport. He had tied the plane down beside his truck, near the unlit airport office, when he heard a thin but demanding "meow." As he stepped to the wide porch, a dark little creature leaped up on the rail right in his face, mewing with desperation. She was tortoiseshell, mixed black and brown. Her big yellow eyes were frightened. She was thin, she was cold, she was hungry; she was lonely for human help.

Pat, with the thought that we were soon to move across country, that we were already looking for a happy new home for Lucy where she would be less confined than in Carmel, did the next best thing to bringing the kitten home. He fed her his remaining sandwich, found an empty box, made a bed for her with his warm flight jacket. He found a bowl in the office, and gave her water. He set up her new home on the wide porch beside the warm purr of the Coke machine, which she could creep behind in case a stray dog came looking. He left her there, curled in the bed--but when he opened his truck door she flew into the front seat, with that desperate and demanding cry. He put her back in her bed. This happened three times, but she was fast as lighting and totally determined. The fourth time he gave up, collected his jacket, and brought her home. He named her ELT, for Emergency Landing Transmitter, the alarm device that screams for assistance when a plane goes down. She'd screamed for rescue, all right. And she got it.

Lucy wasn't pleased at the new arrival. We shut ELT in the small bedroom, with water and food and a sandbox--we let the two get acquainted slowly, sniffing under the door, then pushing paws under. Soon enough Lucy would tolerate her, but Lucy's little thread of jealousy never quite vanished. ELT was, for one thing, wilder than Lucy, storming up the bookcases, walking on the overhead beams, thoroughly trashing my desk. Her favorite sport was to chase a flock of half-tame Canada geese from the lawn where they were grazing into the lake, the geese flapping and scolding. She would go right in the water after them, up to her belly, would stand watching them swim away--then would come in through the cat door dripping mud, highly pleased with herself.

Lucy and ELT made the move to California with me, via Delta, while Pat flew the 180 out, with a longtime California friend--again, two pilots, no room for cats or wives. That long two-day flight would have been miserable for the cats. I had arranged to board them with a veterinarian right in Carmel, only a few blocks from my motel. Every day I walked up to spend an hour or so with them. The staff gave us an empty office, shut the door and left us to play and cuddle. I rented a car from Rent-A-Wreck, too, as our house was not right in the village. It was on a hillside about a mile away, with a fine, long view of green hills, of a land preserve that would never be built on. The small house was old and needed work, but we bought it for that vast, open view.

Shirley at her desk with ELT, Carmel, California, 1990s

Shirley at her desk with ELT, Carmel, California, 1990s

Before Pat arrived, when I'd had the house cleaned and painted, and newly carpeted, I waited for the movers, got things settled, then brought the cats home. The next day I picked Pat up at the local private airport. He had rented a hangar for the 180, and he spent the next few years doing a lot of flying. We both knew the day would come when he couldn't fly any more, as it does with every pilot, and we tried not to think about that. But now, besides flying the 180, he also flew commercially to Alaska every spring to salmon fish with his nephew, and to Georgia each fall to hunt deer with a small group of probation officers--keeping a satisfying connection with close friends. And how we enjoyed that freezer full of salmon and venison.

The first thing we did when we moved into the Carmel house was hire an architect and engineer to finish the tall, looming space beneath the hillside structure, to strengthen it against possible slides and earthquake, and to close the cavernous basement into a lower floor. This gave the little house a nice two-bedroom guest area with large windows. The cats tolerated the carpenters' noise of hammers and circular saws, and so did I as I worked on the fourth book in the "Joe Grey" series, and then the fifth--Cat to the Dogs--and that's when ELT joined Joe Grey.

She was already hanging out in my study while Lucy went out to hunt. I had set up different height bookshelves so the cats could climb to the highest unit, and I arranged one shelf open on both sides against the window so they could see me or see out as they chose. ELT spent a lot of time there; it was then that she appeared in the story without my bidding. I could not start to write without pictures flashing though my mind of her sudden surprising role in the action--while she, herself, sat beside my monitor watching, as if to make sure I paid attention. She entered Cat to the Dogs as a frightened and nameless young feral running the hills, dreaming mythical dreams from the tales she'd heard while following a wild clowder of speaking cats. But now she is looking for more than dreams: she yearns for a human to love her. For someone who would understand and keep the secret of a lonely, speaking kitten.